When the good news broke in mid-March, the effect on our collective mood was positively therapeutic - the beginning of a turn away from fear and toward resilience. We’d been gobsmacked by the reality of how unprepared our institutions were to handle the novel virus, COVID-19. Quarantine, the novel solution, was still being robustly resisted, and discouragement about the future was widespread. The biggest issue was determining how many people were positive for the disease; insufficient testing and delays in processing them were creating a bottleneck. Without this information, containing and treating the pandemic seemed insurmountable. Everyone felt helpless.

Throughout the country, most hospitals and local labs don’t have the equipment to carry out the testing, so all the specimens from our region were being shipped to a lab in North Carolina, necessitating packing, shipping, checking in, testing, then reversing the process to return. There was also a shortage of the necessary chemical reagents. The backlog was increasing daily.

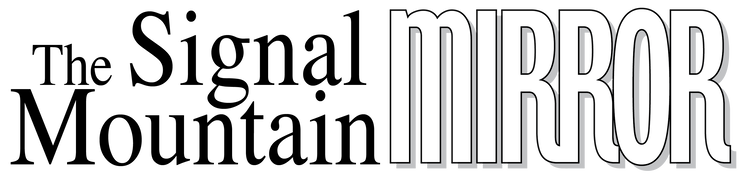

Scientists/teachers Dr. Elizabeth Forrester and Dr. Dawn Richards had been “following the story from its inception,” out of concern for their students at Baylor School, especially those who board, said Forrester. They and their colleague, Dr. Mary Loveless, teach advanced science courses, such as molecular method, biomedical research, and engineering design, at Baylor, and thanks to an endowment from the estate of Elizabeth Weeks, the school has an astoundingly well-equipped laboratory. (The credentials of these exceptional teachers are listed at the end of the article).

Forrester, recognizing they already had the equipment needed to test for the virus, called Richards, the chairperson of Baylor Research, and said simply, “We can do this.” Richards agreed. “We wanted to help,” Forrester said, and because they’re local, she knew it would really speed up the process. At the same time, their students were watching as they carried out practice testing. “Our students realize[d] we had the capabilities in the laboratory. They’re smart! We knew they’d figure it out,” said Richards.

Baylor had to become certified by CDC, sort out legal issues, and comply with federal and state regulations. Due to the crisis, some regulations had been relaxed or ceded to the states, which created more confusion. The school was equipped to process about 65 tests a day, but if they could obtain the resources to “scale up” (add more equipment) they could increase that number considerably. Countless conversations and piles of paperwork followed. There were “lots of obstacles, roadblocks, long days, and late nights to figure it out,” Richards recalled, and Forrester added, “When we hit one roadblock, we would just problem-solve around it.”

They wanted to “have the largest impact on the entire community” if possible, said Richards, and Mary Catherine Robbins, director of Baylor’s Health Center, was instrumental in establishing a partnership with Hamilton County. That was their goal - they all wanted to do as much as they could to help. Forrester put it this way: “The question wasn’t, ‘How can we do this?’ It was, ‘How can we NOT do this.’”

Baylor possesses very sophisticated equipment (a nucleic acid extractor, an RNA transcriber, a biological safety cabinet, laminar flow hoods) that is used to process test specimens. They carry out an assay - an analysis to determine if a specific substance is present. For COVID-19, the first step is to extract the RNA from the specimen. Using a specific protocol, reagents (chemical compounds) are used to transcribe the RNA into DNA, which allows detection of coronaviruses. Specimens are picked up by a medical courier from doctors’ offices and hospitals, then delivered to Baylor. “Processing is less than four hours,” said Forrester, so the results can be returned the same day.

To accomplish this, a zealous team supported the women. “So many people around us have said ‘how can I help?’ and got right to work,” said Richards. One of them is Dr. Loveless, a PhD in biomedical engineering. “I am supporting Dawn and Elizabeth in their efforts by continuing manufacturing effort,” Loveless said. Because Baylor has a Form2 3D printer, she is “seeking approval to manufacture [an FDA-approved ND swab] to prevent a shortage in test kits.” She is also discussing future projects with her students for model design for swab sample capture, material selection for personal protection equipment (PPE), and processes for medical devices.

Like all teachers, these three continue during this crisis to work with students via technology, so this work is in addition to their regular duties. They are all wives and mothers, as well. “Our families are really stepping up,” said Forrester. Richards’ daughters “have been doing the laundry for weeks. They know we are leaving the house each day because we’re trying to help.” Forrester lives on Lookout and has three sons who attend Baylor and St. Nicolas. Richards’ daughter also attends Baylor; her son is in third grade at Nolan Elementary on Signal. And Loveless has two children, ages 5 and 7.

Recently, Grace McKenney, a Baylor alum and current premed student at University of Pennsylvania, volunteered to serve as “director of operations, working with onsite Health Department volunteers to coordinate patient information and reporting,” said Richards, and Forrester added, “She has been a godsend.” As they waited for one last instrument, two other scientists, Dr. Clint Smith and Dr. Alyssa Summers, have also been there, helping them prepare to increase capacity for testing to 300-plus.

As the news spread of their efforts, people came forward to contribute in whatever way possible. “The whole community is supporting us, offering to bring lunch, make dinner for our families,” said Forrester. They’ve received scores of emails and even got a call from someone offering to donate his stimulus check. “That almost brought us to tears,” she said.

Their initiative and willingness to serve was just what the doctor ordered: an injection of hope, that local testing would enable health professionals to deal with the virus more quickly, with a booster of pride, that our city has such capable and creative educators who will step up on our behalf. What role models they are, for their students and for all of us. Elizabeth Forrester summed it up perfectly: “We are all doing our part.” So must we.

Dr. Dawn Richards has an M.S. in Oceanography: Biogeochemical cycling and a Ph.D. in Microbial Ecology. Her interests include microbial community composition in soil, water, and biological systems and antibiotic resistance in the environment.

Dr. Mary Loveless has a B.S. in Computer Science: Computer Engineering and M.S./Ph.D. degrees in Biomedical Engineering. Her interests include embedded systems, mathematical modeling, and imaging.

Dr. Elizabeth Forrester has a B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and a Ph.D. in Cancer Biology from Vanderbilt University. Her interests include mammary tumorigenesis and metastasis, molecular genetics and epigenetics.

by Carol Lannon

Throughout the country, most hospitals and local labs don’t have the equipment to carry out the testing, so all the specimens from our region were being shipped to a lab in North Carolina, necessitating packing, shipping, checking in, testing, then reversing the process to return. There was also a shortage of the necessary chemical reagents. The backlog was increasing daily.

Scientists/teachers Dr. Elizabeth Forrester and Dr. Dawn Richards had been “following the story from its inception,” out of concern for their students at Baylor School, especially those who board, said Forrester. They and their colleague, Dr. Mary Loveless, teach advanced science courses, such as molecular method, biomedical research, and engineering design, at Baylor, and thanks to an endowment from the estate of Elizabeth Weeks, the school has an astoundingly well-equipped laboratory. (The credentials of these exceptional teachers are listed at the end of the article).

Forrester, recognizing they already had the equipment needed to test for the virus, called Richards, the chairperson of Baylor Research, and said simply, “We can do this.” Richards agreed. “We wanted to help,” Forrester said, and because they’re local, she knew it would really speed up the process. At the same time, their students were watching as they carried out practice testing. “Our students realize[d] we had the capabilities in the laboratory. They’re smart! We knew they’d figure it out,” said Richards.

Baylor had to become certified by CDC, sort out legal issues, and comply with federal and state regulations. Due to the crisis, some regulations had been relaxed or ceded to the states, which created more confusion. The school was equipped to process about 65 tests a day, but if they could obtain the resources to “scale up” (add more equipment) they could increase that number considerably. Countless conversations and piles of paperwork followed. There were “lots of obstacles, roadblocks, long days, and late nights to figure it out,” Richards recalled, and Forrester added, “When we hit one roadblock, we would just problem-solve around it.”

They wanted to “have the largest impact on the entire community” if possible, said Richards, and Mary Catherine Robbins, director of Baylor’s Health Center, was instrumental in establishing a partnership with Hamilton County. That was their goal - they all wanted to do as much as they could to help. Forrester put it this way: “The question wasn’t, ‘How can we do this?’ It was, ‘How can we NOT do this.’”

Baylor possesses very sophisticated equipment (a nucleic acid extractor, an RNA transcriber, a biological safety cabinet, laminar flow hoods) that is used to process test specimens. They carry out an assay - an analysis to determine if a specific substance is present. For COVID-19, the first step is to extract the RNA from the specimen. Using a specific protocol, reagents (chemical compounds) are used to transcribe the RNA into DNA, which allows detection of coronaviruses. Specimens are picked up by a medical courier from doctors’ offices and hospitals, then delivered to Baylor. “Processing is less than four hours,” said Forrester, so the results can be returned the same day.

To accomplish this, a zealous team supported the women. “So many people around us have said ‘how can I help?’ and got right to work,” said Richards. One of them is Dr. Loveless, a PhD in biomedical engineering. “I am supporting Dawn and Elizabeth in their efforts by continuing manufacturing effort,” Loveless said. Because Baylor has a Form2 3D printer, she is “seeking approval to manufacture [an FDA-approved ND swab] to prevent a shortage in test kits.” She is also discussing future projects with her students for model design for swab sample capture, material selection for personal protection equipment (PPE), and processes for medical devices.

Like all teachers, these three continue during this crisis to work with students via technology, so this work is in addition to their regular duties. They are all wives and mothers, as well. “Our families are really stepping up,” said Forrester. Richards’ daughters “have been doing the laundry for weeks. They know we are leaving the house each day because we’re trying to help.” Forrester lives on Lookout and has three sons who attend Baylor and St. Nicolas. Richards’ daughter also attends Baylor; her son is in third grade at Nolan Elementary on Signal. And Loveless has two children, ages 5 and 7.

Recently, Grace McKenney, a Baylor alum and current premed student at University of Pennsylvania, volunteered to serve as “director of operations, working with onsite Health Department volunteers to coordinate patient information and reporting,” said Richards, and Forrester added, “She has been a godsend.” As they waited for one last instrument, two other scientists, Dr. Clint Smith and Dr. Alyssa Summers, have also been there, helping them prepare to increase capacity for testing to 300-plus.

As the news spread of their efforts, people came forward to contribute in whatever way possible. “The whole community is supporting us, offering to bring lunch, make dinner for our families,” said Forrester. They’ve received scores of emails and even got a call from someone offering to donate his stimulus check. “That almost brought us to tears,” she said.

Their initiative and willingness to serve was just what the doctor ordered: an injection of hope, that local testing would enable health professionals to deal with the virus more quickly, with a booster of pride, that our city has such capable and creative educators who will step up on our behalf. What role models they are, for their students and for all of us. Elizabeth Forrester summed it up perfectly: “We are all doing our part.” So must we.

Dr. Dawn Richards has an M.S. in Oceanography: Biogeochemical cycling and a Ph.D. in Microbial Ecology. Her interests include microbial community composition in soil, water, and biological systems and antibiotic resistance in the environment.

Dr. Mary Loveless has a B.S. in Computer Science: Computer Engineering and M.S./Ph.D. degrees in Biomedical Engineering. Her interests include embedded systems, mathematical modeling, and imaging.

Dr. Elizabeth Forrester has a B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and a Ph.D. in Cancer Biology from Vanderbilt University. Her interests include mammary tumorigenesis and metastasis, molecular genetics and epigenetics.

by Carol Lannon

RSS Feed

RSS Feed